Adherence practices

Here we suggest some simple practices that can help you and others at your institution to better adhere to current proposed ethical guidelines.

- Start Slow - Starting slow can allow for time to better understand how AI systems work and any possible unexpected consequences.

- Check for Allowed Use - AI model responses are often not transparent about using code, text, images and other data types that may violate copyright. They are currently not necessarily trained to adequately credit those who contributed to the data that may help generate content.

- Use Multiple AI Tools - Using a variety of tools can help reduce the potential for ethical issues that may be specific to one tool, such as bias, misinformation, and security or privacy issues.

- Educate Yourself and Others - To actually comply with ethical standards, it is vital that users be educated about best practices for use. If you help set standards for an institution or group, it strongly advised that you carefully consider how to educate individuals about those standards of use.

Disclaimer: The thoughts and ideas presented in this course are not to be substituted for legal or ethical advice and are only meant to give you a starting point for gathering information about AI policy and regulations to consider.

Start Slow

Launching large projects using AI before you get a chance to test them could lead to disastrous consequences. Unforeseen challenges have already come up with many uses of AI, so it is wise to start small and do evaluation first before you roll out a system to more users.

This also gives you time to correspond with legal, equity, security, etc. experts about the risks of your AI use.

Tips for starting slow

For decision makers about AI users:

- Consider an early adopters program to evaluate usage.

- Educate early users about the limitations of AI.

- Consider using AI first for more specific purposes.

- Consult with experts about potential unforeseen challenges.

- Continue to assess and evaluate AI systems over time.

For decision makers about AI developers:

- Consider developing tools for more simple specific tasks, rather than broad difficult tasks.

- Consider giving potential users guidance about using the tool for simpler tasks at first.

- Continue to assess and evaluate AI systems over time.

Example 4 Real-World Example

IBM created Watson, an AI system that participated and won on the game show Jeopardy! and showed promise for advancing healthcare. However IBM had lofty goals for Watson to revolutionize cancer diagnosis, yet unexpected challenges resulted in unsafe and incorrect responses.

IBM poured many millions of dollars in the next few years into promoting Watson as a benevolent digital assistant that would help hospitals and farms as well as offices and factories. The challenges turned out to be far more difficult and time-consuming than anticipated. IBM insists that its revised A.I. strategy — a pared-down, less world-changing ambition — is working ((lohr_what_2021?)).

See here for addition info: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8678513

Check for Allowed Use

When AI systems are trained on data, they may also learn and incorporate copyrighted information or protected intellectual property. This means that AI-generated content could potentially infringe on the copyright or protection of trademarks or patents of the original author. For more extreme examples, if an AI system is trained on an essay or art or in some cases even code written by a human, the AI system could generate responses that are identical to or very similar to that of the original author, which some AI tools have done. Regardless, even training AI tools on copyrighted information where the responses are still relatively different, if the AI system uses this content without permission from the original author, this could constitute copyright or trademark infringement Brittain and Brittain (2023).

Example 5 Open AI is facing lawsuits about using writing from several authors to train ChatGPT without permission from the authors. While this poses legal questions, it also poses ethical questions about the use of these tools and what it means for the people who created content that helped train AI tools. How can we properly give credit to such individuals?

The lawsuits are summarized by Brittain and Brittain (2023):

The lawsuit is at least the third proposed copyright-infringement class action filed by authors against Microsoft-backed OpenAI. Companies, including Microsoft (MSFT.O), Meta Platforms (META.O) and Stability AI, have also been sued by copyright owners over the use of their work in AI training

The new San Francisco lawsuit said that works like books, plays and articles are particularly valuable for ChatGPT’s training as the “best examples of high-quality, long form writing.”

OpenAI and other companies have argued that AI training makes fair use of copyrighted material scraped from the internet.

The lawsuit requested an unspecified amount of money damages and an order blocking OpenAI’s “unlawful and unfair business practices.”

AI poses questions about how we define art and if AI will reduce the opportunities for employment for human artists. See here for an interesting discussion, in which it is argued that AI may enhance our capacity to create art. This will be an important topic for society to consider.

Tips for checking for allowed use

For decision makers about AI use:

- Be transparent about what AI tools you use to create content.

- Ask the AI tools if the content it helped generate used any content that you can cite.

Possible Generative AI Prompt: Did this content use any content from others that I can cite?

For decision makers about AI development:

- Obtain permission from the copyright holders of any content that you use to train an AI system. Only use content that has been licensed for use.

- Cite all content that you can.

Use Multiple AI Tools

Only using one AI tool can increase the risk of the ethical issues discussed. For example, it may be easier to determine if a tool incorrect about a response if we see that a variety of tools have different answers to the same prompt. Secondly, as our technology evolves, some tools may perform better than others at specific tasks. It is also necessary to check responses over time with the same tool, to verify that a result is even consistent from the same tool.

Tips for using multiple AI tools

For decision makers about AI use:

- Check that each tool you are using meets the privacy and security restrictions that you need.

- Utilize platforms that make it easier to use multiple AI tools, such as https://poe.com/, which as access to many tools, or Amazon Bedrock, which actually has a feature to send the same prompt to multiple tools automatically, including for more advanced usage in the development of models based on modifying existing foundation models.

- Evaluate the results of the same prompt multiple times with the same tool to see how consistent it is overtime.

- Use slightly different prompts to see how the response may change with the same tool.

- Consider if using tools that work with different types of data maybe helpful for answering the same question.

For decision makers about AI development:

- Consider if using different types of data maybe helpful for answering the same question.

- Consider promoting your tool on platforms that allow users to work with multiple AI tools.

Educate Yourself and Others

There are many studies indicating that individuals typically want to comply with ethical standards, but it becomes difficult when they do not know how (Giorgini et al. (2015)). Furthermore, individuals who receive training are much more likely to adhere to standards (Kowaleski, Sutherland, and Vetter (2019)).

Properly educating those you wish to comply with standards, can better ensure that compliance actually happens.

It is especially helpful if training materials are developed to be especially relevant to the actually potential uses by the individuals receiving training and if the training includes enough fundamentals so that individuals understand why policies are in place.

Example 6 Real-World Example

A lack of proper training at Samsung lead to a leak of proprietary data due to unauthorized use of ChatGPT by employees – see https://cybernews.com/news/chatgpt-samsung-data-leak for more details:

“The information employees shared with the chatbot supposedly included the source code of software responsible for measuring semiconductor equipment. A Samsung worker allegedly discovered an error in the code and queried ChatGPT for a solution.

OpenAI explicitly tells users not to share “any sensitive information in your conversations” in the company’s frequently asked questions (FAQ) section. Information that users directly provide to the chatbot is used to train the AI behind the bot.

Samsung supposedly discovered three attempts during which confidential data was revealed. Workers revealed restricted equipment data to the chatbot on two separate occasions and once sent the chatbot an excerpt from a corporate meeting. Privacy concerns over ChatGPT’s security have been ramping up since OpenAI revealed that a flaw in its bot exposed parts of conversations users had with it, as well as their payment details in some cases. As a result, the Italian Data Protection Authority has banned ChatGPT, while German lawmakers have said they could follow in Italy’s footsteps.”

Tips to educate yourself and others

For decision makers about AI use:

- Emphasize the importance of training and education.

- Recognize that general AI literacy to better understand how AI works, can help individuals use AI more responsibly.

- Seek existing education content made by experts that can possibly be modified for your use case.

- Consider how often people will need to be reminded about best practices. Should training be required regularly? Should individuals receive reminders about best practices especially in contexts in which they might use AI tools.

- Make your best practices easily findable and help point people to the right individuals to ask for guidance.

- Recognize that best practices for AI will likely change frequently in the near future as the technology evolves, education content should be updated accordingly.

For decision makers about AI development:

- Emphasize the importance of training and education.

- Recognize that more AI literacy to better understand security, privacy, bias, climate impact and more can help individuals develop AI more responsibly.

- Seek existing education content made by experts that can possibly be modified for your use case.

- Consider how often people will need to be reminded about best practices. Should training be required regularly? Should individuals receive reminders about best practices especially in contexts in which they might develop AI tools.

- Make your best practices easily findable and help point people to the right individuals to ask for guidance.

- Recognize that best practices for AI will likely change frequently in the near future as the technology evolves, education content should be updated accordingly.

We have also included an optional section for new developers about considerations for testing and training data to ensure accurate assessment of performance.

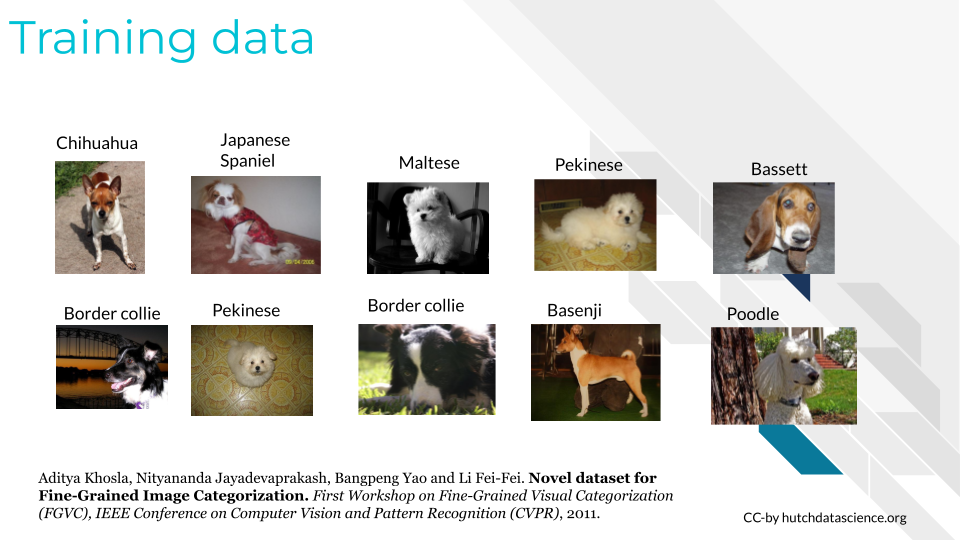

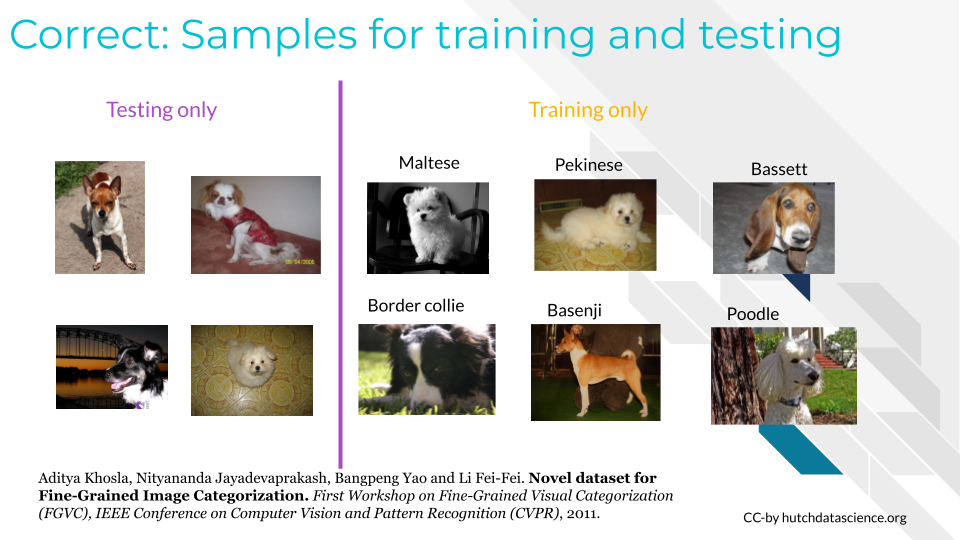

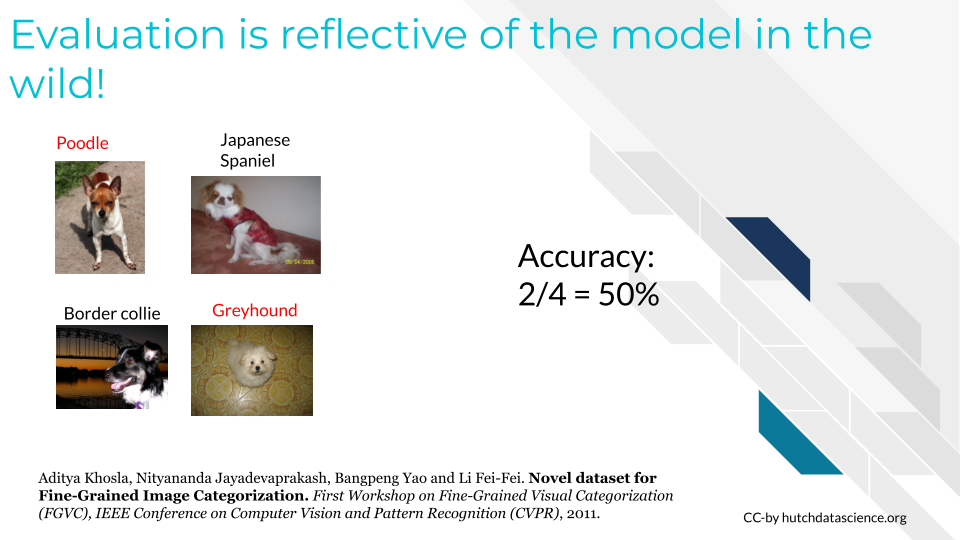

Effective use of Training and Testing data

Summary

Here is a summary of all the tips we suggested:

- Disclose when you use AI tools to create content.

- Be aware that AI systems may behave in unexpected ways. Implement new AI solutions slowly to account for the unexpected. Test those systems and try to better understand how they work in different contexts.

- Adhere to restrictions for use of data and content created by AI systems where possible, citing the AI system itself and learning how the tool obtained permission for use can help reduce risk.

- Cross-check content from AI tools by using multiple AI tools and checking for consistent results over time. Check that each tool meets the privacy and security restrictions that you need.

- Emphasize training and education about AI and recognize that best practices will evolve as the technology evolves.

Overall, we hope that these suggestions will help us all use AI tools more responsibly. We recognize however, that as this is emerging technology and more ethical issues will emerge as we continue to use these tools in new ways. AI tools can even help us to use them more responsibly when we ask the right additional questions, but remember that human review is always necessary. Staying up-to-date on the current ethical considerations will also help us all continue to use AI responsibly.