def cool_function(x):

return x + 1

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

for i, element in enumerate(my_list):

my_list[i] = cool_function(element)

print(my_list)[4, -34, 99, 3.3, 1, -2]You now have hands-on experience writing For-Loops, Conditional Statements, and Functions. That is the core of what the course is about. In this section, we will examine alternative and powerful ways people use shortcuts to write these statements.

You have been writing For-Loops to modify or create Lists. To modify an existing list, you write a pattern like this:

def cool_function(x):

return x + 1

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

for i, element in enumerate(my_list):

my_list[i] = cool_function(element)

print(my_list)[4, -34, 99, 3.3, 1, -2]To create a list based on another list:

new_list = []

for element in my_list:

new_list.append(cool_function(element))

print(new_list) [5, -33, 100, 4.3, 2, -1]When the final product of a For-Loop is a List, it is common to write a short-hand via a “List Comprehension”. The syntax looks like this:

[<expression> for <var> in <iterable>]For our first example, the For-Loop would be rewritten as:

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

my_list = [cool_function(element) for element in my_list]For our second example, the For-Loop would be rewritten as:

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

new_list = [cool_function(element) for element in my_list]Here’s how the Python interpreter would work through this:

my_list, and assign it as element.cool_function(element), and the output value is stored as the first element of our output list.my_list and assign it as element. Repeat steps 2, 3 until we’re done.List comprehensions encourages the following:

Readability that the output product is a List.

Encouragement of writing functions for the body of the loop. A list comprehension can only take in one expression.

Note that you don’t need to use a function when invoking a list comprehension. You could have something like:

[element / 2 for element in my_list][1.5, -17.5, 49.0, 1.15, 0.0, -1.5]We can add a second flavor of complexity into creating Lists in which a condition needs to be met in order for the element to be in the new list.

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

new_list = []

for element in my_list:

if element > 0:

new_list.append(cool_function(element))

print(new_list)[4, 99, 3.3]We would use the following List Comprehension syntax:

[<expression> for <var> in <iterable> if <condition>]Here’s how it looks like:

my_list = [3, -35, 98, 2.3, 0, -3]

new_list = [cool_function(element) for element in my_list if element > 0]

print(new_list)[4, 99, 3.3]Here’s how the Python interpreter would work through this:

my_list, and assign it as element.element > 0. If this is True, then proceed to step 3. If this is False, don’t evaluate and proceed to the next member of my_list and assign it as element.cool_function(element), and the output value is stored as the first element of our output list.my_list and assign it as element. Repeat steps 2-4 until we’re done.One iterable data structure that we haven’t discussed in this course is how to use iteration on is Series - the column of a Dataframe. An extremely common iteration pattern on Series is to apply a function to each element of the Series to transform the data. Many existing functions are built to with a Series object in mind, such as the following example:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

simple_df = pd.DataFrame(data={'id': ["AAA", "BBB", "CCC", "DDD", "EEE"],

'case_control': ["case", "case", "control", "control", "control"],

'measurement1': [2.5, 3.5, 9, .1, 2.2],

'measurement2': [0, 0, .5, .24, .003],

'measurement3': [80, 2, 1, 1, 2]})

simple_df| id | case_control | measurement1 | measurement2 | measurement3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AAA | case | 2.5 | 0.000 | 80 |

| 1 | BBB | case | 3.5 | 0.000 | 2 |

| 2 | CCC | control | 9.0 | 0.500 | 1 |

| 3 | DDD | control | 0.1 | 0.240 | 1 |

| 4 | EEE | control | 2.2 | 0.003 | 2 |

We make a log transformation:

np.log(simple_df.measurement1)0 0.916291

1 1.252763

2 2.197225

3 -2.302585

4 0.788457

Name: measurement1, dtype: float64The function np.log(x) takes in a Series as input. But what about functions that we already have but the input it takes in is an element of Series, such as cool_function(x)? We could write a For-Loop to do that, but it is actually discouraged in terms of performance. Rather, what is encouraged is to use the mapping function.

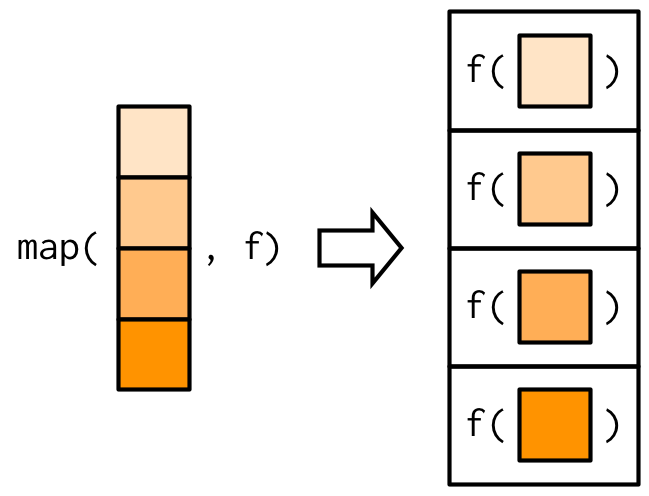

A map (also known as a functional) is a function that takes in an iterable data structure and function as inputs and applies the function on the data structure, element by element. It maps your input iterable data structure to an output data structure based on the function.

Visually, it looks like this:

Or,

You can use the .map() method for Series to do this:

simple_df.measurement1.map(cool_function)0 3.5

1 4.5

2 10.0

3 1.1

4 3.2

Name: measurement1, dtype: float64This map style of writing iterations is known as “functional programming”. You write a function that can work for a single element of your data, and you can scale it up iteratively via a mapping function.

One of the most common use-case of the .map() method is for data recoding. For instance, suppose we want to create cutoffs for the column “measurement1” using the following function:

def measurement1_cutoff_rule(x):

if x > 0 and x < 2:

return "low"

elif x >= 2 and x < 7:

return "medium"

elif x >= 7:

return "high"

else:

return "unknown"We can map this function measurement1_cutoff_rule() to each element of “measurement1”:

simple_df.measurement1.map(measurement1_cutoff_rule)0 medium

1 medium

2 high

3 low

4 medium

Name: measurement1, dtype: objectSometimes, a function you want to define is short and not used by any other part of the program, which is common in the .map() method. For instance, cool_function()’s content is only one line of code, and perhaps cool_function() is never used again elsewhere in the code. Defining def cool_function() seems a bit excessive.

Turns out, you can define a very short function to be used just one time:

simple_df.measurement1.map(lambda x: x + 1)0 3.5

1 4.5

2 10.0

3 1.1

4 3.2

Name: measurement1, dtype: float64The lambda statement signifies that you are writing a single-expression function that is going to be used only once. The variable x is the input argument, and x + 1 is the body of the function. The output of the single expression is the return value of the function. Nice and simple!

We’ve talked about writing For-Loops, List-Comprehensions, Maps, and we know there are existing functions and methods that can be used on an entire data structure. So which iteration method should you use when you are working with data? Here are some general guidelines, in order of consideration:

When you can, use existing functions and methods that can carry out the iteration task. For example, if you want to compute the mean value of a Dataframe’s column, use the .mean() method. It will be much more efficient iterating via a For-Loop. These existing functions and methods from standard modules are highly optimized to be efficient beyond the scope of this class.

If you need to use a function on each element of a dataframe’s column, such as data recoding, use the .map() method to help with the iteration.

If your desired output is a List, consider writing a List Comprehension. They tend to perform a bit faster than For-Loops because you have told it in advance what the resulting data structure will be.

When working with iterable data structures, For-Loops are the most general purpose.

If you really want to use a For-Loop on a Series, you can use the .items() method on a Series to get the index and value, similar to the enumerate() function. Then when you modify a column, you would need to use the dataframe’s .loc[ ] attribute to access the elements to be modified. Here is a simple example:

for i, value in simple_df.measurement1.items():

print(f"Index : {i}, Value : {value}")

simple_df.loc[i, "measurement1"] = value * 2Index : 0, Value : 2.5

Index : 1, Value : 3.5

Index : 2, Value : 9.0

Index : 3, Value : 0.1

Index : 4, Value : 2.2Exercise for week 5 can be found here.