Chapter 9 DNA Methods

This chapter is in a beta stage. If you wish to contribute, please go to this form or our GitHub page.

9.1 Learning Objectives

9.2 What are the goals of analyzing DNA sequences?

9.3 Comparison of DNA methods

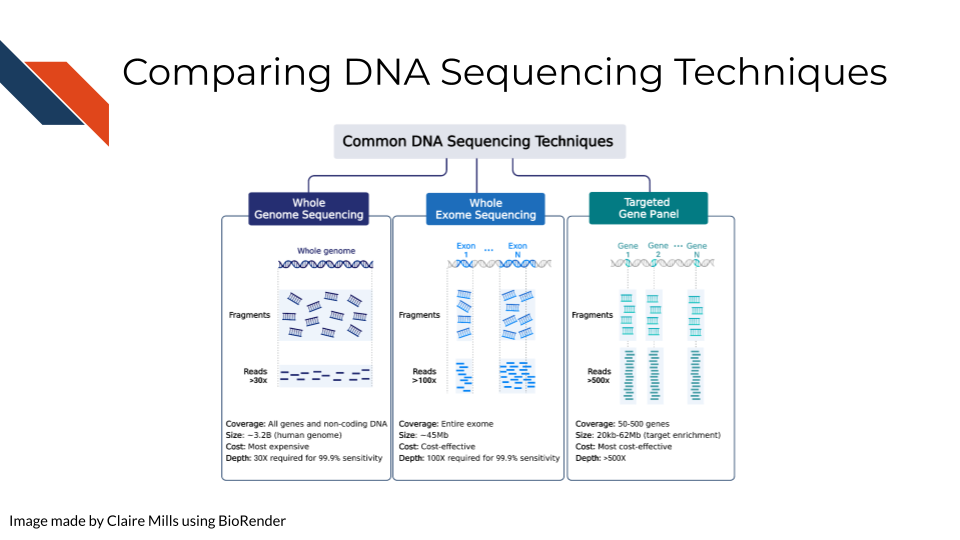

Compared to WXS and Targeted Gene Sequencing, WGS is the most expensive but requires the lowest depth of coverage to achieve 95% sensitivity. In other words, WGS requires sequencing each region of the genome (3.2 billion bases) 30 times in order to confidently be able to pick up all possible meaningful variants. (Sims et al. 2014) goes into more depth on how these depths are calculated.

Compared to WXS and Targeted Gene Sequencing, WGS is the most expensive but requires the lowest depth of coverage to achieve 95% sensitivity. In other words, WGS requires sequencing each region of the genome (3.2 billion bases) 30 times in order to confidently be able to pick up all possible meaningful variants. (Sims et al. 2014) goes into more depth on how these depths are calculated.

Alternatively, WXS is a more cost effective way to study the genome, focusing places in the genome that have open reading frames – aka generally genes that are able to be expressed. This focuses on enriching for exons and not introns so splicing variants may be missed. In this case, each gene must be sequenced 80-100x for sufficient sensitivity to pick up meaningful variants.

In targeted gene sequencing, a panel of 50-500 regions of interest are selected. This technique is very applicable for studying a set of specific genes of interest at great depth to identify all varieties of mutations within those specific genes. These genes must be sequenced at much greater depth (>500x) to confidently identify all meaningful variants. This page from Illumina also provides information regarding sequencing depth considerations for different modalities.

Additional references: WGS: (Bentley et al. 2008) WES: (Clark et al. 2011) Targeted: (Bewicke-Copley et al. 2019)

9.4 How to choose a DNA sequencing method

Before starting any sequencing method, you likely have a research question or hypothesis in mind. In order to choose a DNA sequencing method, you will need to consider a few items in balance of each other:

9.4.1 1. What region(s) of the genome pertain to your research question?

Is this unknown? Can it be narrowed down to non-coding or coding regions? Is there an even more specific subset of interest?

9.4.2 2. What does your project budget allow for?

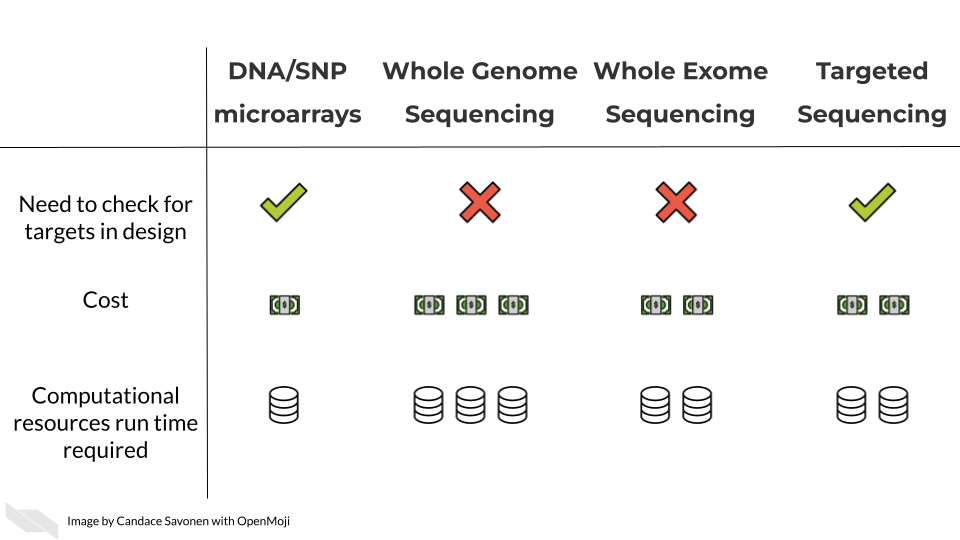

Some methods are much more costly than others. Cost is not only a factor for the reagents needed to sequence, but also the computing power needed to process and store the data and people’s compensation for their work on the data. All of these costs increase as the amounts of data that are collected increase. For more information on computing decisions see our Computing in Cancer Informatics course.

9.4.3 3. What is your detection power for these variants?

Detecting DNA variants is not simply a matter of yes or no, but a confidence level due to sequencing errors in data collection. Are the variants you are looking for very rare and/or small (single nucleotide or very few copy number differences)? If so you will need more samples and potentially more sequencing depth to detect these variants with confidence.

9.5 Strengths and Weaknesses of different methods

Is not much known about DNA variants in your organism or disease in question? In this instance you may want to cast a large net to explore more variants by using WGS.

If previous research has identified sections of the genome that are of interest to your research question, then it’s highly advisable to not sequence the entire genome with WGS methods. Not only will whole genome sequencing be more costly, but it will decrease your statistical power to discover true positive variants of interest and increase your chances of discovering false positive variants. This is because multiple testing correction needs to be applied in instances where many tests are being done currently. In this instance, the tests being performed are across the whole genome.

If your research question does not pertain to non-coding regions of the genome or splicing, then its advisable to use WXS. Recall that only about 1-2% of the genome is coding sequences meaning that if you are uninterested in noncoding regions but still use WGS then 98-99% of your data will be uninteresting to you and will only serve to increase your chances of finding false positives or cost you a lot of funding. Not only does sequencing more of the genome take more money and time but it will be more costly in time and resources in terms of the computing power needed to analyze it.

Furthermore, if you are able to narrow down even further what regions are of interest this would be better in terms of cost and detection abilities. A targeted sequencing panel or DNA microarray are ideal for assaying known groups of targets. DNA microarrays are the least costly of all the methods to identify DNA variants, but with both targeted sequencing and DNA microarray you will need to find or create a custom probe or primer set. Ideally a probe or primer set that hits your regions of interest already exists commercially but if not, then you will have to design your own – which also costs time and money.

In these upcoming chapters we will discuss in more detail each of these methods, what the data represent, what you need to consider, and what resources you can consult for analyzing your data.