Chapter 8 Annotating Genomes

This chapter is in a beta stage. If you wish to contribute, please go to this form or our GitHub page.

8.1 Learning Objectives

In this chapter, we are going to discuss methods that affect every genomic method and may take up the majority of your time as a genomic data analyst: Annotation.

We know that the sequencing or array data is not useful on its own – for our human minds to comprehend it and apply it to something we need a tangible piece of information to be attached to it. This is where annotation comes in. At best annotation helps you and others interpret genomic data. At its worst, its a time consuming activity that, done incorrectly, can lead to erroneous conclusions and labeling.

Proper annotation requires an understanding of how the annotation data you are using was derived as well as the realization that all annotation data is constantly changing and the confidence for these data are never 100%. Some organism’s genomes are better annotated than others but nearly all are at least somewhat incomplete.

8.2 What are reference genomes?

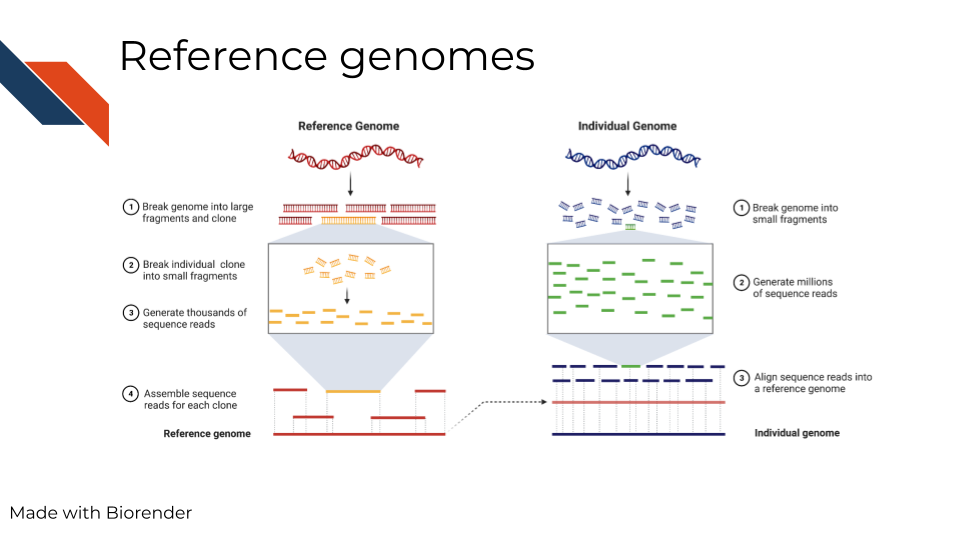

Every individual organism has its own DNA sequence that is unique to it. So how can we compare organisms to each other? In some studies, sequencing data is obtained and the genome is built de novo (aka from scratch) but this takes a lot of time and computing power. So instead, most genomic studies use the imperfect method of comparing to a reference genome. Reference genomes are built from prior data and available online. They inherently have biases in them. For example, human genomes are generally not made from diverse populations but instead from mostly males of european descent. It is inherently bad for both ethical and scientific reasons to to have genome references that are too white. For more on the problems with reference genomes, read this.

In summary, reference genomes are used for comparison and as a ‘source of truth’ of sorts, but its important to note that this method is biased and better alternatives need to be realized.

8.3 What are genome versions?

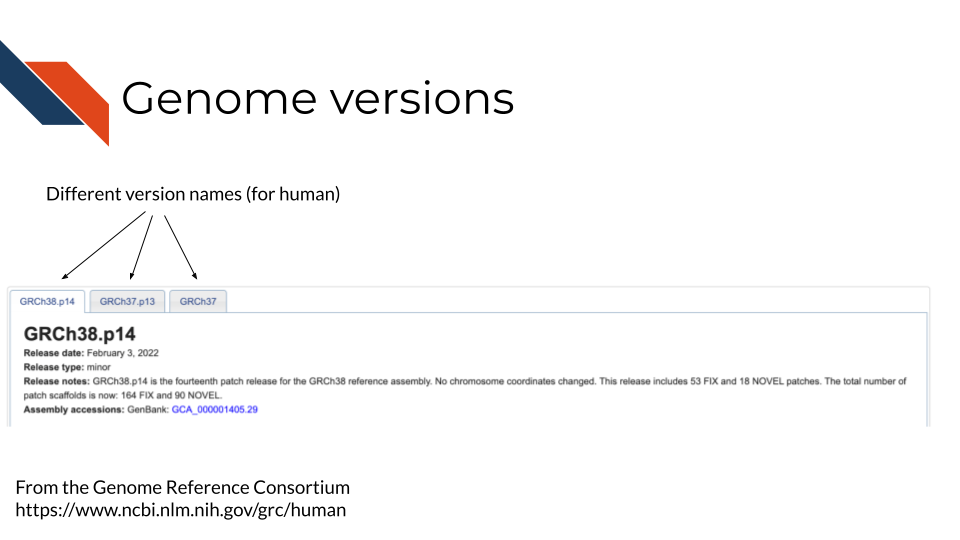

If you are familiar with software development, or have used any app before, you’re familiar with software updates and releases. Similarly, the genome has updates and releases as continued cloning and assemblies of organisms teaches us more. In the image below we are showing an example of what a genome version may be noted as (note that different databases may have different terminology – here we are showing the Genome Reference Consortium). You may also notice on their website it shows the date the genome version was released and what was fixed.

The details of how genome versions are fixed and released are not really of concern for your data analysis. This is merely to explain that genomes change and what is most important in your analysis is that:

- You choose one genome version and consistently use it in all your analyses.

- Choose a genome version that the rest of your field has generally had a consensus on and is also using. Generally this means sticking with major releases of a genome instead of always going with the latest version. Most databases will try to point you to their major release, so just stick with that. We will point you where you can find genome annotation for a lot of the major organisms.

8.4 What are the different files?

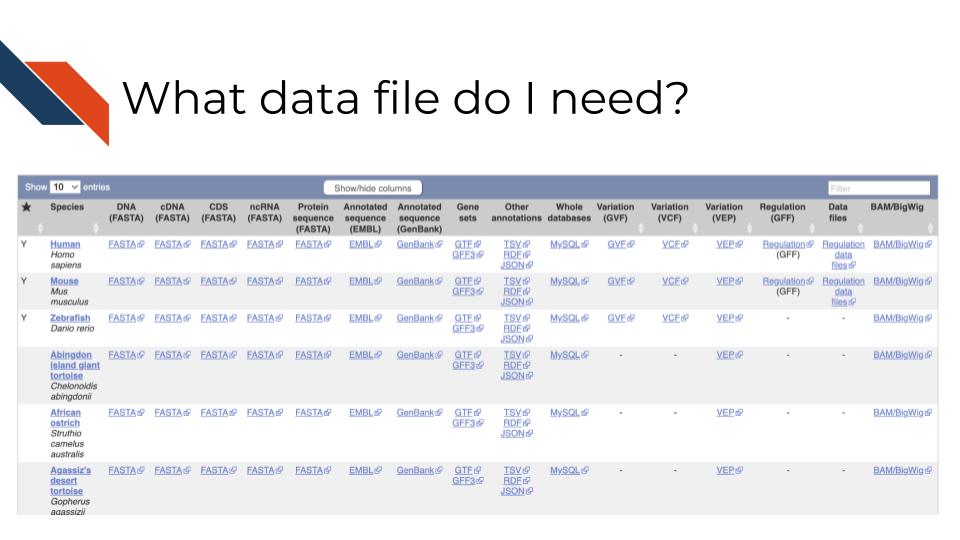

Although we can’t walk you through every organism and database set up, we will walkthrough the files and structure of one example here.

In the above screenshot, from Ensembl, it shows different organisms in the rows, but also a variety of different files across the columns. In this example, DNA reference to the DNA sequence of the organism’s genome, but cDNA refers to complementary DNA – aka DNA that has been reversed transcribed from RNA. If you are working with RNA data you may want to use the cDNA file. Whereas CDS files are referring to only coding sequences and ncRNA files are showing only non coding sequences. Most of these files are FASTA files. Gene sets are also their own annotation files called GTF or GFF files. Ensembl provides more detailed information about what these files contain, but briefly, each row is a feature and has information describing that feature such as genomic locations, the relevant feature type (gene, coding sequence, pseudogene, etc.), and the gene ID or name. For a reminder on what these different file types are see the previous chapter.

Depending on the tool you are using, the data file and type you need will vary. Some tools have these data built in or are compatible with other packages that have annotation. If a tool automatically includes annotation within it, you will need to ensure that any additional tools you are using are also pulling from the same genome and version. Look into a tool’s documentation to find out what genome versions it is based on. If it doesn’t tell you at all, you don’t want to be using that tool. You cannot assume that cross genome analyses will translate.

8.4.1 How to download annotation files

For another database example we’ll look at the human data on ENA’s servers. Note that if you see FTP that just means “Fast Transfer Protocol” and it just means its where you can get the files themselves. For more on computing lingo, you can take our Computing in Cancer Informatics course.

There’s many ways you can download these files and they are described here. In summary:

- If you don’t feel comfortable using command line, you can use the browser downloader for ENA here

- If you are using command line to write a script, then you can write use the wget or curl instructions described here. Be sure to read the README files to understand what it is you are downloading.

Also note that if you are working from a high power computing cluster or other online server, these annotation files may already be available to you. You don’t want to take up more computing resources by downloading extra files, so check with an administrator or informatics expert who also uses the cluster or cloud to check if the annotation files already exist in your workspace.

8.5 Considerations for annotating genomic data

8.5.1 Make sure you have the right file to start!

- Is the annotation from the right organism? You may think this is a dumb question, but its very critical that you make sure you have the genome annotation for the organism that matches your data. Indeed the author of this has made this mistake in the past, so double check that you are using the correct organism.

- Are all analyses utilizing coordinates from the same genome/transcriptome version? Genome versions are constantly being updated. Files from older genome versions cannot be used with newer ones (without some sort of liftover conversion). This also goes for transcriptome and genome data. All analysis need to be done using the same genomic versions so that is ensured that any chromosomal coordinates can translate between files. For example, it could be in one genome version a particular gene was said to be at chromosome base pairs 300 - 400, but in the next version its now been changed to 305 - 405. This can throw off an analysis if you are not careful. This type of annotation mapping becomes even more complicated when considering different splice variants or non-coding genes or regulatory regions that have even less confidence and annotation about them.

8.5.2 Be consistent in your annotations

- If at all possible avoid making cross species analyses - unless you are an evolutionary genomics expert and understand what you are doing. But for most applications cross species analyses are hopeful wishing at best, so stick to one organism.

- Avoid mixing genome/transcriptome versions. Yes there is liftover annotation data to help you identify what loci are parallel between releases, but its really much simpler to stick with the same version throughout your analyses’ annotations.

8.5.3 Be clear in your write ups!

Above all else, not matter what you end up doing, make sure that your steps, what files you use, and what tool versions you use are clear and reproducible! Be sure to clearly link to and state the database files you used and include your code and steps so others can track what you did and reproduce it. For more information on how to create reproducible analyses, you can take our reproducibility in cancer informatics courses: Introduction to Reproducibility and Advanced Reproducibility in Cancer Informatics.

8.6 Resources you will need for annotation!

8.6.3 Command line based tools

8.6.3.1 R-based packages:

GenomicRanges - useful for manipulating and identifying sequences.

GO.db - Gene ontology annotation

A full list of Bioconductors annotation packages - contains annotation for all kinds of species and versions of genomes and transcriptomes.