Chapter 2 Clinical Data Types

2.2 Clinical data is unique

Clinical data comes from a wide variety of sources and as such, requires careful consideration when designing, collecting, and analyzing this data. Unlike domains such as Finance or other areas in the sciences which predominantly use structured data, clinical data is often heterogeneous, integrating quantitative measurements, categorical data, subjective narratives from patient notes, and objective observations from doctor notes and even possible image analysis. Free text adds a layer of complexity with unstructured information, reflecting subjective patient experiences or qualitative insights from healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the contrast between patient and doctor notes reflects the dual perspectives of symptoms and formal diagnoses. In essence, clinical data’s unique blend of structured and unstructured components, along with its multidisciplinary nature, necessitates specialized methodologies for comprehensive analysis and interpretation in the realm of healthcare.

2.3 Major clinical data types

Clinical data can come in many different forms, including demographics, diagnoses, lab results, vital signs, medication records, procedures, genetic reports, images, scanned documents, and notes written by physicians, nurses, and other clinicians. Although any of these types of information might theoretically be available for use in clinical research, some sources are more accessible than others. As they are often stored directly in electronic medical record systems, notes, demographics, observations (labs, medications, procedures, and vitals), and images are the easiest data to work with, and are the focus of most Electronic Health Record (EHR) data research efforts.

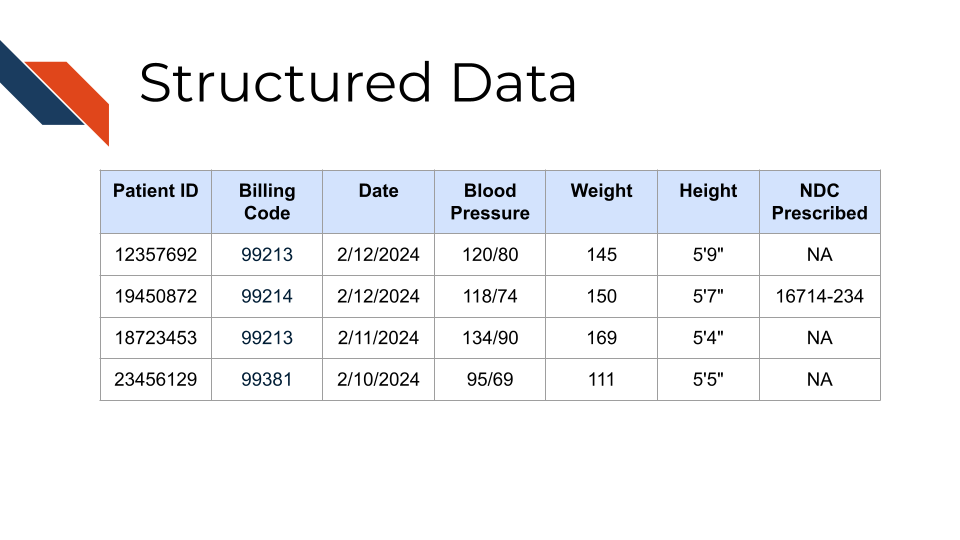

2.3.1 Structured Data

Observational and demographic data are often collectively referred to as “structured data”, as they are stored in electronic health record databases and often provided to researchers in tabular form. Although details may vary based on the type of EHR being used, the customizations to the EHR for the specific environment in which data was collected, and any pre-processing that might be done by institutional research offices prior to providing data to researchers, details are likely to be familiar across contexts. Structured data types frequently used in EHR research include demographics, diagnoses, lab values, procedures, vitals, and medication records. Often provided as tables indexed off of a patient or visit ID, these tables often include timestamps and other supporting descriptors. For example, medication orders might specify the drug name, class, dose, unit, quantity, route, frequency, and other instructions.

Structured data tables often describe entries in terms of codes from standardized vocabularies. Diagnoses might be described with codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) vocabulary, lab tests with Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), medications with National Drug Code (NDC), and procedures with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. These terms, or “billing codes”, provide a common foundation that can be invaluable for identifying patients with a specific disease or who have received specified medications, particularly when integrating data from multiple sources.

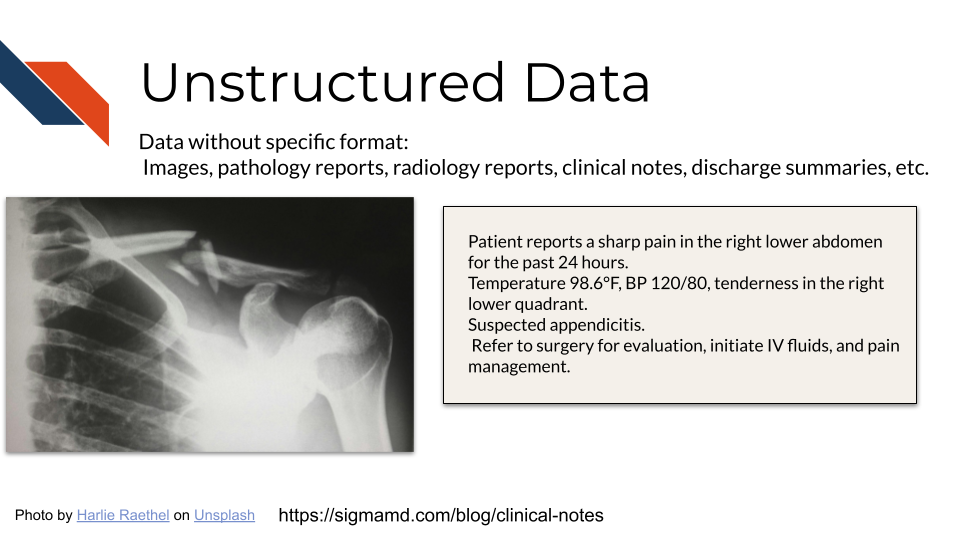

2.3.2 Unstructured Data / Clinical Notes

Clinical notes are, perhaps unsurprisingly, generally shared as seemingly straightforward text files. However, the simple format should not be taken as a suggestion that the data are easy to interpret. Some EHR systems contain literally dozens of types of notes, covering specialties such as pathology or surgery; specific moments in care such as admission or discharge; particular procedures such as colonoscopies; patient-provider interactions such as telehealth or phone encounters, and many others. In addition to differing in content, these sources may have different layouts and formats, ranging from free-form reports to structured SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, and plan) formats or even templated procedure reports. Understanding the types of notes available in a given context and where relevant data might be found is a key step in effectively using clinical notes.

When used in EHR research, both structured data and clinical notes are generally de-identified to protect patient privacy. Patient ID numbers might be replaced with new identifiers, with linkages maintained by institutional “honest brokers” (Dhir et al. 2008) charged with providing clinical data for research purposes. In some cases, dates may be changed as well. Clinical notes are generally “de-identified” through specialized software designed to remove names, dates, locations, and other sensitive details. Researchers working with institutions to access clinical data should be sure to understand local data de-identification practices.